If there is one concept in the development world that has gained momentum in recent years, it is undoubtedly the term API.

There is no self-respecting project that does not have its API, public or private, or that makes use of third-party APIs to obtain information or integrate services in a more or less simple way.

But what is an API?

The acronym API stands for the term Application Programming Interface, which we could translate as application programming interface. An API is nothing more than a set of functions offered by a system, which, by combining them in an appropriate way, allows us to create applications or new functionalities.

Types of APIs

But an API can not only take the form of an HTTP service, the concept is much broader than that. For example, in the object oriented programming (OOP) paradigm, the set of public methods of a class can be considered your API.

When we download a third-party library into our project, the set of services and functions that we can use is also the API of this library.

If we develop applications for Android, iOS, Linux, Windows, MacOS... these systems offer APIs that allow us to interact with the system so that we can do things like open windows, capture system notifications, integrate our app with the system so that it has a native look and feel, include new actions in menus... etc.

And, of course, the set of endpoints that allow us to interact with an HTTP service, is also an API. In this case an HTTP API.

HTTP APIs

The API concept is the same, but in this case the functionalities instead of being in a library that we have imported or being part of a system for which we want to develop, are in an external server that offers us these functionalities and the way to communicate with the server is through the HTTP protocol.

Given this feature, it is very important to know how the HTTP protocol works, since understanding the details of HTTP will allow us to understand how the API works.

Let's take a quick look at the most important concepts of the HTTP protocol.

HTTP Protocol

The HTTP protocol is a network communication protocol. It is based on requests and responses (requests y responses) that must follow a specific format. It is a protocol not connection-oriented, that is, after obtaining the response to a request, the connection is closed instead of being kept waiting for further requests. In other words, it does not maintain the state.

It is a multimedia protocol, since it supports different formats for both request and response data: HTML, CSV, JSON, XML, images, PDFs, audio, video...

URLs

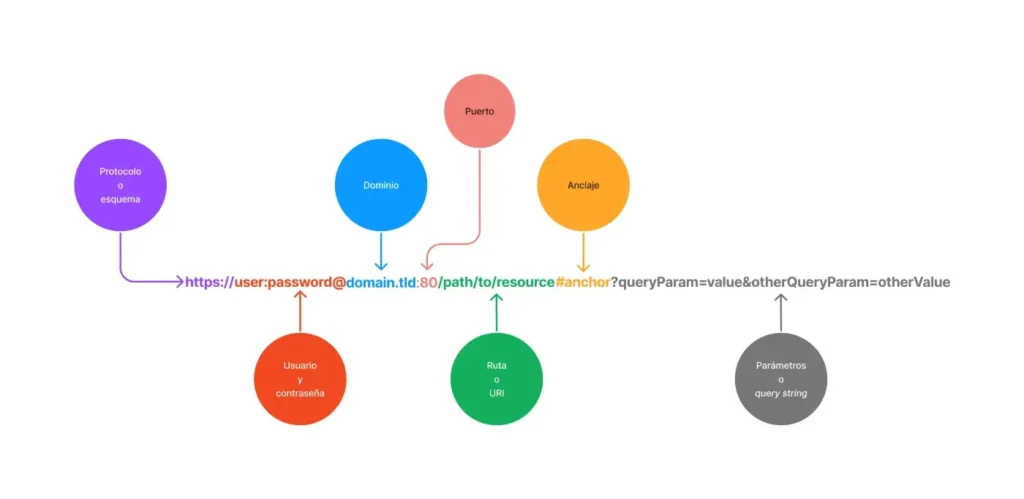

The URL is possibly the most important component of HTTP, as it is the string that will represent an address. The acronym URL stands for Uniform Resource Locator, o uniform resource locator in plain English. As its name indicates, it is a resource locator, a string that allows us to identify a resource univocally. Let's see its parts:

- Protocol or outline: this part is mandatory and indicates the protocol or service we are going to use. Since URLs are used in other protocols, such as FTP, SSH, NFS and many others, indicating the protocol is a must. In addition, each protocol has a default port defined, so if it has not changed for some reason, we can save putting the port in the URL.

In this case, the protocol will be HTTP or HTTPS (the encrypted version of the HTTP protocol). - Username and password: although it is not very common, we can use the URL itself to authenticate, although it is not very secure. This is more commonly used in other protocols, but it is worth knowing that this option exists.

The user and the password are separated by the character of the colon o colon. The at (@) is used to separate the password from the domain.

This part is obviously optional. - Domain and TLD: The domain name is the most common part of a URL and indicates the server to which we want to connect. It is composed of 3 parts:

- Subdomain: is optional. Usually indicates different services or functions within the same server: www, ftp, api, assets, etc..

- Domain: is the most known part, the name of the server to which we connect: Google, Amazon, Microsoft...

- TLD: Top Level Domain, i.e., the already known.es,.com,.net...

The domain and TLD are mandatory. - Port: Usually this part of the URL is implicit with the protocol, but sometimes (for example in development) it is possible that we are using a different port to serve our service. The correct way to indicate the port is by means of the character of the colon o colon and the port number.

This part is optional, as mentioned above. - Route, path or URI: is the string that identifies a resource within the service. Sometimes we will hear it referred to as URI (Universal Resource Identifier) o path. It is usually a slash-separated string indicating the location of a resource.

This part is mandatory although, if we do not incorporate it, it is assumed that we are accessing the root, represented by the slash /. - Anchoring, anchor o fragment: this only makes sense within the context of the web (HTML to be more precise). It is used to indicate which section within a document we want to refer to with the URL.

It is totally optional. - Parameters or query string: is a set of variables that we pass the URL. Usually with the intention of parameterizing the response as, for example, in the case of using pagination. To indicate that we start passing parameters we use the character ?, and to separate one parameter from another we use the character &.

This is entirely optional.

Requests

As its name suggests, a request is the act of asking a service to perform a certain action and respond with the result.

In the case of HTTP requests, these are composed of:

- Verb: indicates the type of action to be performed, we will see this in depth later.

- URL: route to which we are requesting the action.

- Headers: are parameters that give us information about the request itself or its requirements. We can, for example, specify in which format we want the response or in which language. We will go into more detail on this later.

- Body: in the case of write requests, this is where the content of our request goes. It can be in different formats, but we have to specify by means of a header which format we have used.

Responses

As a counterpart to a request, we have the response. The response follows a very similar format to the request, except that in this case it does not incorporate a verb, but a status code (status code) that defines the result of the request. Obviously, the response still includes a body with the data we have requested or extra information. The status code is a form of classify the response.

Let's see what elements make up an HTTP response:

- Status code: indicates the type of response. We will go into detail later.

- Headers: are parameters that give us information about the response itself, such as its format, language, address of the new resource created or other information related to the cache.

- Body: in the case of responses to read requests, this is where the requested content goes. It can be in different formats, but we have to specify by means of a header which format we have used.

Headers

As we have already mentioned, headers are part of both requests and responses, and these serve both to provide information about them and to configure them. For example, by means of request headers we can tell the server what response format we want (Accept), or in which language (Locale), in which format we are sending data (Content-Type), where we come from (Referrer) or even who we are (Auth) and which client we use (User-Agent). With the responses we can do the same, and include, in addition, information about the server (Server), the compression used (Content-Enconding), the cache (Cache-*) and a long etcetera.

The well-known cookies are also included in the headers of both responses and requests.

If we run out of headers for what we need, we can always define our own headers by presetting X- to the name of our header (although this is not recommended).

A list of all available headers can be found at Wikipedia - List of HTTP headers

Status codes

Status codes are numeric values included in the responses that help us determine whether the response was successful, failed because of the request or failed because of the service.

The status codes are grouped into 5 blocks:

As can be seen in the graphic above, these 5 blocks of status codes are differentiated by the first digit, which is the one that indicates what type of response we have obtained. The next two digits give us more specific information about the response. Let's take a look at some examples.

1xx Informative

- 100 Continue

- 101 Switching Protocols

2xx Success

- 200 OK

- 201 Created

- 202 Accepted

- 204 No Content

- 206 Partial Content

3xx Redirection

- 301 Moved Permanently

- 302 Found

- 304 Not Modified

4xx Customer Error

- 400 Bad Request

- 401 Unauthorized

- 402 Payment Required

- 403 Forbidden

- 404 Not Found

- 405 Method Not Allowed

- 409 Conflict

- 412 Precondition Failed

- 413 Request Entity Too Large

- 415 Unsupported Media Type

- 422 Unprocessable Entity

- 428 Precondition Required

5xx Server Error

- 500 Internal Server Error

- 501 Not Implemented

- 502 Bad Gateway

- 503 Service Unavailable

- 504 Gateway Timeout

- 505 HTTP Version Not Supported

A more complete list can be found at this link: RestApiTutorial - Status Codes or in Wikipedia - Status Codes

Verbs

Now that we have talked about URLs, let's see how to interact with them. The HTTP protocol uses a set of verbs or actions to be used depending on the type of request we want to carry out, such as, for example, a data read or a write.

Let's look at the most common verbs:

- GET: is used to read content. It is very common for URLs queried via GET to support parameters of query string. These petitions lack a petition body.

- POST: eThis is the request used to create new resources. It is the only operation not idempotent, If we execute it more than once, the state of our system will have changed (we will have created two resources), something that does not happen with the rest of the verbs. This is why, among other things, POST requests cannot be cached.

POST requests have a body, and that is where the information we will use to write the new resource goes. - PUT: Like POST, this request writes data, but in this case to update a resource completely, that is, to replace its content with the content that comes in the body of the request.

- DELETE: is the verb we use when we want to delete a resource.

- PATCH: is similar to PUT but does not replace the resource completely, but only partially modifies it. It is necessary to specify a request format indicating the changes to be made to the resource. There is currently no standard for this and it is a rarely used verb.

- HEAD: There are times when we are only interested in knowing the result of a GET request without seeing its content. With the HEAD verb we can obtain only the status code of a request. This can be useful, for example, to determine if a resource exists or not without the need to obtain it.

- OPTIONS: this verb allows us to know which verbs a URL supports, that is, if we can perform GET, POST and PUT, or only POST, or only GET or any possible combination.

Other aspects of an HTTP API

One of the main characteristics of the APIs mentioned above is that they are multimedia and this means that they support different formats both in the request and response data: HTML, CSV, JSON, XML, images, PDFs, audio, video...

Here are some examples.

Request forms

Requests usually follow simple input formats, usually JSON or XML, although it could very well be YAML, TOML, CSV or any type of file.

The advantage of JSON or XML is that they are sufficiently structured formats to represent information in a way that is relatively understandable to a person and easily processed by a machine.

The format of the request is indicated in the header Content-Type, This is important so that when the petition is processed the backend know how to process the input data.

If the XML format is used, since it is a metalanguage that allows different schemas to be specified, it is essential that it includes the schema used to indicate to the backend how to interpret the input.

If we want to attach files, they must be encoded. Usually the following encoding is used base64, although any type of encoding could be valid as long as it is indicated in a header such as Content-Encoding the encoding algorithm. Recall that coding is a reversible process that consists in translate from one format to another, algorithms for hashing such as MD5 or SHA1 would not work.

Response Formats

For the format of the answers there are a series of standards that allow us to develop clients in a simpler way. Let's take a look at some of them.

- JSON-API

JSON-API is a documented response format for APIs. Explaining it in detail would give rise to an entire post dedicated to it, so we will only comment on a series of details. It usually consists of a series of top-level elements or root elements, e.g. links, The pagination information, with all the information related to the pagination in case you are returning lists of resources. Another essential element is data, which in turn can be an object of type resource object or an array of such objects (if the answer is a collection).

If the request has failed, it will not contain any of these elements, and will instead have an element errors with the errors that have occurred.

I recommend taking a look at the complete specification with examples on the official website, links can be found in the Bibliography section or the link at the beginning of this section. - HAL

This format has not really made it past the draft or draft stage. draft, so implementations can be found, but are not guaranteed to be supported or compatible. In many ways it is very similar to JSON-API.

It could be said that JSON-API used JSON-HAL as the basis for defining its format.

Again, I recommend taking a look at the complete specification with examples in the draft. Links can be found in the Bibliography section or the link at the beginning of this section.

Conclusion

We have reviewed several of the main features of HTTP APIs. It's a good time to leave it here and reflect on what we've learned and look at our own APIs and think about how we can improve them.

This series of posts will continue to be open, soon we will talk about some types of APIs, such as REST, RESTful, GraphQL... we will talk about accessory but not less important topics, such as authentication, security, serialization, documentation, versioning...

We hope that all this knowledge we have been gathering will be useful to you and that you will continue reading the rest of the series!

In future posts...

- REST APIs

- GraphQL APIs

- Authentication and session management

- API Documentation

_ Bibliography

RESTful Web APIs: Services for a Changing World

REST API design principles

JSON-API specification

Draft JSON-HAL specification